Container rain

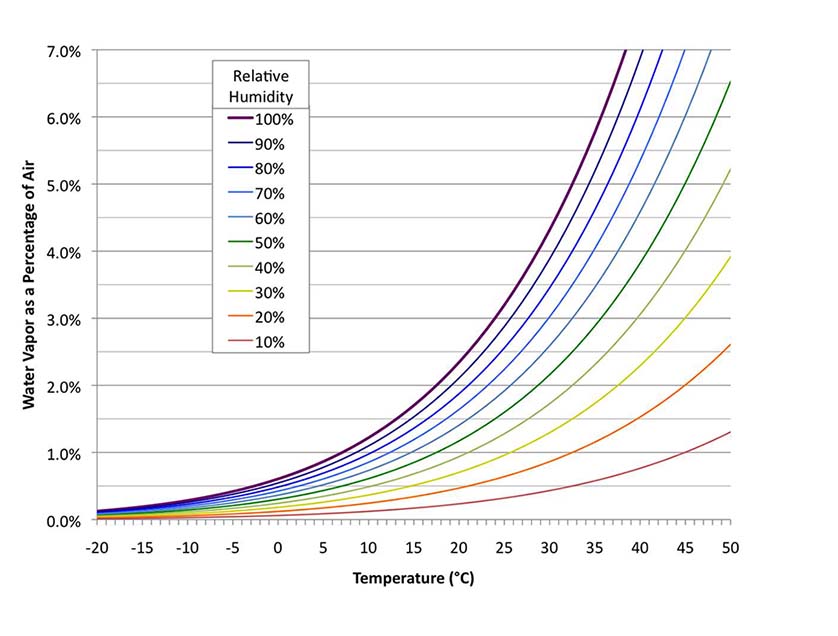

Container rain, also known as container sweat, is the term used to describe the condensation that takes place within a sealed shipping container resulting in moisture damage to imported goods. Warm air can hold more moisture than cold air. When the temperature goes down, the relative humidity (percentage of the moisture that can be retained by the air – moisture-holding capacity – at a given temperature and pressure without condensation) will increase. If the air is cooled enough, some of the moisture may condense. The dew point is the temperature to which air must be cooled to become saturated with water vapor. It is assumed that air pressure and water content are constant. When cooled further, the airborne water vapor will condense to form liquid water (dew). When air cools to its dew point through contact with a surface that is colder than the air, water will condense on the surface. A temperature drop of 5° is often enough to cause problems. Water will condense on the coolest available surface, which usually is on the container ceiling or walls. From there it may drip down onto the cargo and cause damage.

Given that the temperature and pressure can fluctuate drastically from day to night, the container rain phenomenon can happen as often as every 24 hours during the journey of the supply chain.

Shipping in containers is an economical and safe way of shipping most types of cargo. But putting cargo into an enclosed steel box also means a constant risk of moisture damage caused by container rain for almost every kind of cargo on every voyage.

For container rain to happen, two main conditions are needed:

● Temperature variations during shipment

● Excess moisture

All containers contain moisture from the time of loading and no container is completely airtight. Moisture will move in and out of the container during the voyage known as ‘container breathing’. Temperature variations are difficult to remove and have a high-cost mitigation.

What about excess moisture? By reducing the amount of moisture entering the container, and by using desiccants to remove moisture from the air, you can prevent the build-up of moisture to levels where it may cause damage. Therefore, you will avoid the effect known as container rain.

Is the container airtight?

A minimum requirement is that the container is in good condition, without holes or damaged doors. This should be checked for every container before loading. The doors are especially vulnerable to damage that may not easily be noticed. Check the ventilation holes. Certainly, no container is airtight, but a container in good condition only allows air and moisture to move in and out of the container slowly. This significantly reduces the amount of moisture moving into the container under common circumstances. Tape the ventilation holes if you are shipping a dry cargo.

During a voyage half-way around the world, the temperature in the container will rise every day and fall every night. This temperature fluctuation means that the air expands during the day, spilling out from the container and then contracts, bringing in new, humid sea air at night. This is what is called container breathing.

Is the container dry?

A container that has been washed before loading may contain a lot of water. Pay special attention to the container floor. All pallets and wooden dunnage will also bring extra moisture into the container. The goods may also contain moisture – especially organic or hygroscopic materials. It is easy to check the moisture content of the wood with a handheld moisture meter.

When the temperature rises in the container during the daytime, the moisture in the floor, pallets, packaging material and goods will evaporate into the air since the relative humidity in the container decreases and can become lower than the equilibrium moisture ratio for the material. The absolute humidity in the air increases which makes the dew point higher and thus to increases the risk of container rain even more.